This blog also appeared on Medium.

Earlier this year I was invited by the Union of Jewish Students to join the Holocaust Educational Trust on their “Lessons from Auschwitz” programme.

After an orientation meeting the week before, I travelled to Poland on Tuesday 15th November with approximately 200 other participants. A group of 19 student officers, including my NUS colleague Shakira Martin, joined school pupils, teachers, HET educators and facilitators.

We landed in Kraków just after 10.30am and in a convoy of buses made our way first of all to the town of Oswiecim, the town immediately beside Auschwitz-Birkenau. Our educator, Sarah, had talked to us in our orientation meeting about the importance of what we don’t see as much as what we do, and I hadn’t quite understood the magnitude of that until we arrived on the site of the Great Synagogue.

This Menorah is all that remains to mark the site of the Great Synagogue

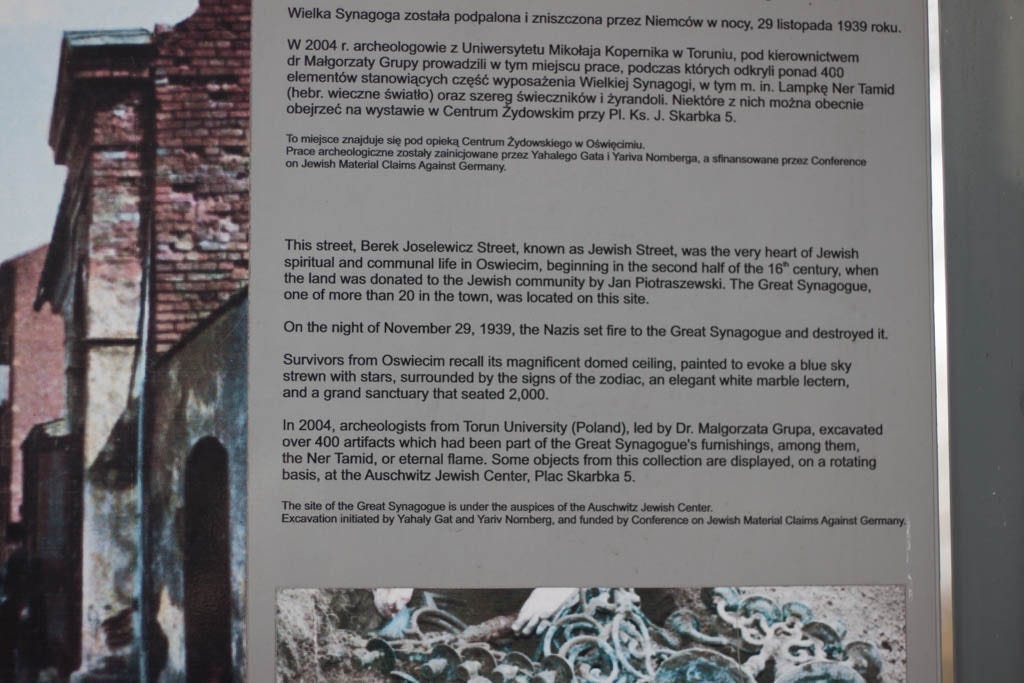

The sign at the site of the Great Synagogue on Berek Joselewicz Street in Oswiecim

Before 1939, Poland was home to some 3 million Jews. Today, that figure is somewhere in the region of 15,000. A vibrant, multicultural community which co-existed in relative harmony before the war, was obliterated. And what of Oswiecim? Is it truly possible that the industrialised death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau operated on the town’s doorstep with nobody aware of what was happening?

The Rabbi who accompanied us, talking about the history of the Great Synagogue

After an explanation of the history of the street we stood in, from the Rabbi who accompanied us, we boarded the buses again to travel on to Auschwitz, and I was startled at how brief our journey was.

What is not there, is as important as what is. The Great Synagogue should sit behind these trees.

The approach to Auschwitz, taken from the bus.

The barbed wire fences with the top hat lampposts were so suddenly in my eyeline to the right, and the trainline to my left, then our buses swung into the car park. The process to enter Auschwitz is quite time consuming with airport-style security, but we soon found ourselves with our guide for the day, Anna.

The notorious 'Arbeit Macht Frei' sign over the entrance to Auschwitz

A rose, left in the fence at the entrance to Auschwitz

The Rabbi had mentioned to us as we stood in Oswiecim that we may be surprised by our reactions, and that there was no correct way to feel as we explored Auschwitz-Birkenau, but as we walked into the camp I felt entirely dislocated from where we were. I couldn’t reconcile my awareness of the horrors of Auschwitz with this grouping of brick buildings, filled with people who were, like me, wrapped up in warm coats and hats & scarves to protect them from the bitter cold, weaving in and out as we explored.

Auschwitz I

It was when we began entering the buildings at Auschwitz that I felt that I was able to begin absorbing where we were and what we were seeing. Every room had artefacts?—?from handwritten registers of detainees, to images?—?including illicit photographs taken by prisoners and smuggled to the outside in an attempt to tell the world of the horrors which were taking place there. I was so overwhelmed by what we were seeing, and felt so rushed, that I took photographs of almost everything. I was struggling to keep up with our group as I tried to see, process, and contemplate everything laid before us. I was particularly hit hard by the huge selection of mugs, plates and cooking pots which had been confiscated from women arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau, who had brought these items to care for their loved ones.

Cooking utensils, confiscated from women arrving at Auschwitz-Birkenau

Confiscated hairbrushes and shaving brushes

Empty canisters containing Zyklon B, which was used to murder people in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau

We approached a room where our guide asked us not to take photographs. We entered the room and followed the directions to move in a circular clockwise fashion to the right, and I became aware that on the left hand side the room was a viewing window. As we reached the top of the room to move towards the window I began to realise in horror that we were looking at piles upon piles of human hair. Long plaits, some still with clasps or ribbons attached, stacked in front of us. I found out later that after Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated, after a consistent programme of destroying evidence had been undertaken by the SS, there still remained nearly 2000 kilogrammes of human hair. In dehumanising and brutalising the prisoners of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazis ensured that they would reap everything possible from their prisoners. The hair was used for a variety of purposes, including making garments.

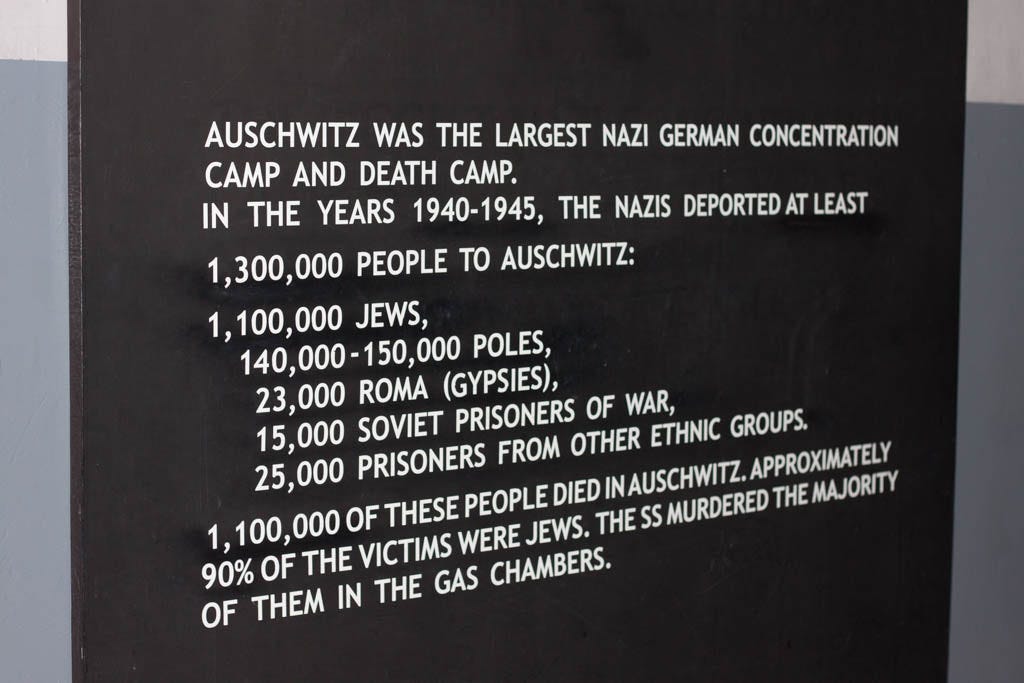

As we moved to leave the building, rows upon rows of photographs of the first prisoners to be detained at Auschwitz lined the walls. Until the Spring of 1943, almost every Auschwitz concentration camp prisoner was photographed for identification. After that date, only German prisoners or occasionally prisoners of other nationalities were photographs. It is important to note here that the Jews deported in mass transports were never photographed. This lack of cataloguing is part of the reason why it is so difficult to put accurate figures on the number of lives lost at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

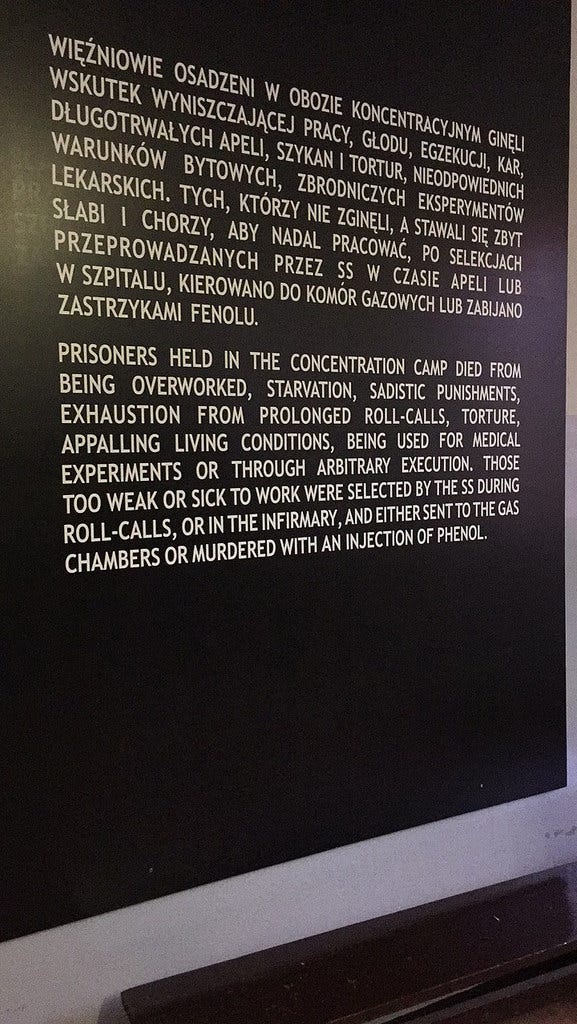

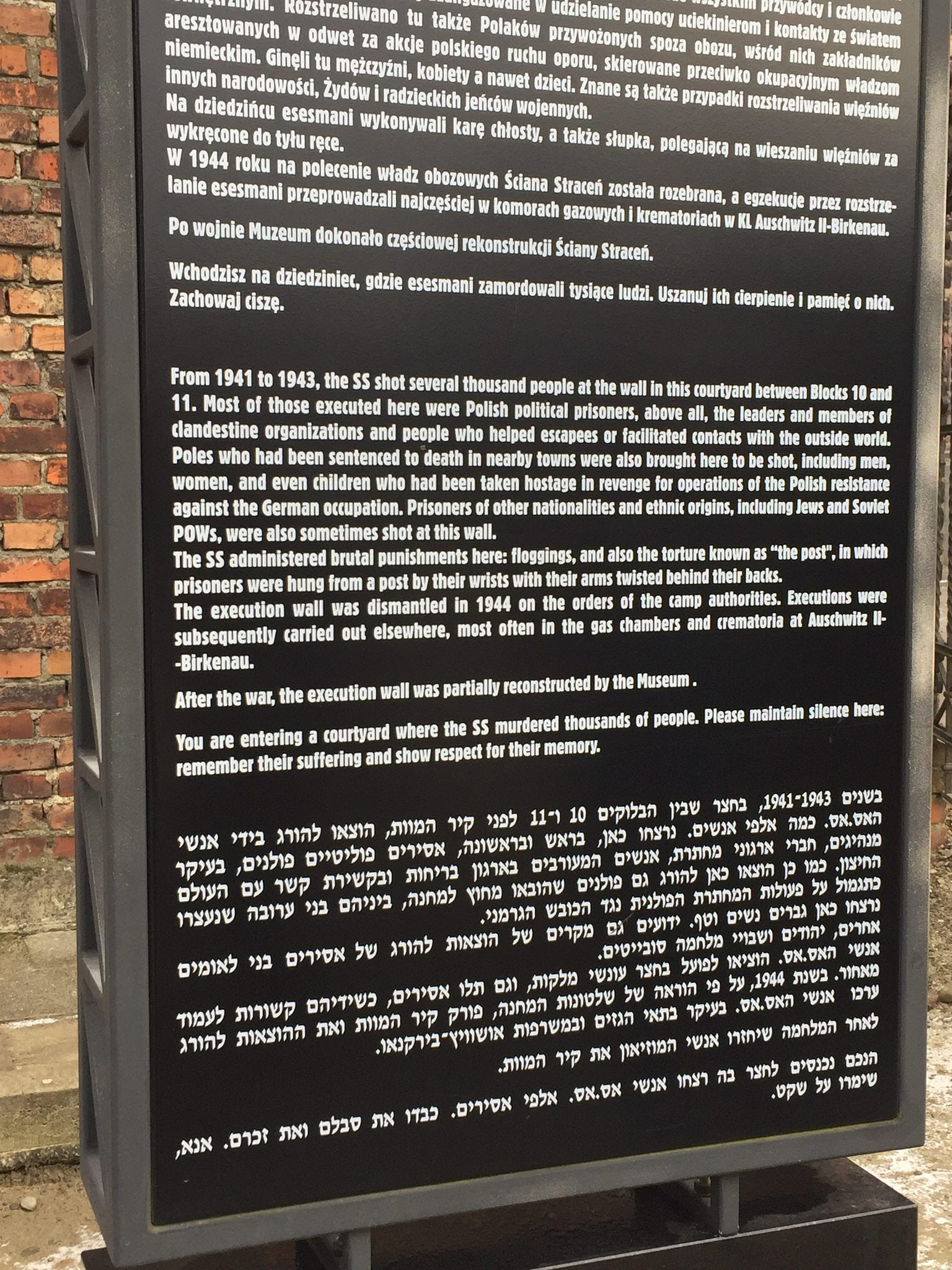

We continued around the camp with Anna talking incessantly, explaining the function of each area of the camp. From the building where women prisoners were used as human guinea pigs for sterilisation experiments, to the courtyard between blocks 10 & 11 where prisoners were subjected to brutal punishments and where the SS murdered thousands of men, women and even children by shooting them.

Flowers and candles left in front of the execution wall

We walked past the space where the cruel daily rollcalls took place, and again I was aware of the juxtaposition of feeling the cold while wrapped up in boots, coat, hat, scarf & gloves and knowing that it was a relatively mild day, compared to the prisoners of Auschwitz who would have had to stand in exactly that spot for hours at a time in their denim camp uniforms at below freezing temperatures. We walked on to the spot where Rudolf Höss, the first Camp Commandant, was hanged after his trial, and saw just how close to the camp he lived with his wife and children. With such unimaginably dehumanising horror just metres from his family home, the situation filled me with many questions about compartmentalisation, and how this terrible human being who oversaw so many deaths and so much cruelty could go home at the end of the day to fulfil a different role as loving father and husband.

I have found it hard to verbalise how I have felt about the trip, but by this stage of the day I was incapable of talking to people. I was aware of Shakira looking at me, and as I met her gaze I could see my despair reflected in her eyes too.

The last part of the first camp was the gas chamber which served there until the larger capacity industrialised gas chambers at Birkenau began operating. We moved through in absolute silence, taking in the enormity of the enclosed space, before boarding the bus to move on to the Birkenau site.

Approaching Birkenau

It was nearly 3.30pm when we got to Birkenau, and it was already dusk. We walked up the railway line towards the overbearing red brick entrance and the stark, open site lay ahead of us.

A row of wooden hut buildings with brick chimneys stood on my right, and behind them rows upon rows of brick chimneys — the only remnants of the buildings which housed thousands of prisoners.

A row of wooden hut buildings with brick chimneys stood on my right, and behind them rows upon rows of brick chimneys — the only remnants of the buildings which housed thousands of prisoners.

These brick chimneys are all that remains of the old wooden huts which housed thousands of prisoners

We visited a couple of the buildings where Anna told us more about the regime of dehumanisation, from several people cramped into a bed, to a routine which regulated how many times a day the prisoners could use the toilet, to how women prisoners would have their period with no access to sanitary protection or even toilet paper, to the meagre “meals” carefully calculated to just keep each person alive for the three months they would usually live for after arriving at Birkenau and being picked for the workforce.

Following the railway line inside Birkenau towards the platform

We left the buildings and followed the railway line up towards the platforms, constructed by prisoners, where the transports filled with people would arrive and where, there on the platform, they would be separated by SS Doctors who would decide with a nonchalant flick of the wrist who would go straight to the gas chambers. Women, children, the elderly, the infirm, would be dead within hours of arriving - if they were not dead already from being forced to endure days of travelling in packed rail wagons like this one with no food, water or toilet facilities.

We continued on, passing over the memorial to the site of Crematorium II. As we viewed, in abject horror, the huge capacity of the buildings specifically created for the mass extermination of individual people, our guide explained to us in the clearest of ways, that we were standing on the largest gravesite in the world, that the ruins of the crematorium and therefore the grounds around us were all saturated with the ashes of over a million people murdered at the hands of the SS.

After we had been to see “Canada” - the buildings named after the land of plenty, where the confiscated belongings were sorted, we went to the administration block where prisoners were processed, and in the last room were hundreds of photographs rescued after Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated. It was an intense end to an intense visit, and I found it very difficult to look at the faces in the photographs.

We moved back to the memorial and there, the Rabbi conducted a ceremony of remembrance. As he blew the shofar and sang the Jewish prayer for the victims of the Holocaust, I felt a surge of emotion at how radical an act it was to conduct worship of the Jewish faith on that site where the Nazis attempted to extinguish Judaism entirely.

Candles were lit by everyone, and left on the railway lines. I lit mine and thought of the family members of my friend Cat, whose Great-Grandmother and Great-Uncle died there.

Lighting my candle

Candles being left on the railway track at Birkenau

Since I came back, I’ve been asked repeatedly, “How was your trip?” by well-intentioned friends, colleagues and family members who smile and look wide-eyed with expectation. The truth is that I can’t answer that question honestly. The trip was one of the most terrible things I have ever experienced. To bear witness, in such a small way really, to the greatest human suffering, has been a challenge emotionally and mentally. I am still struggling to process the sheer scale, and the actions of each individual and bystander who played a role in the Holocaust.

I returned home on Wednesday afternoon and sat down in my home, and the first thing I noticed was that my boots were all muddy. But, struck by the words of our guide Anna, that the whole Birkenau site has human ashes embedded into it, I can’t clean my boots. I’m not sure I will ever be able to.

Vonnie Sandlan

NUS Scotland President 2016-17